In her half-century on earth, Torry Holmesly has been subjected to neglect, violence, eviction and homelessness. So, if you ask her about what life is like in a banking desert, forgive her for looking at you funny.

And yet, Holmesly, 50, is far from a fool. She knows that not having a nearby and trustworthy bank or credit union has cost her — of savings and peace of mind, of her dream of buying a home and, lately, of avoiding a predatory auto loan.

“The banks would come and they go,” says Holmesly, who moved her two daughters to Azle, Texas, in 2009 after a “church lady” met them at a shelter and helped them find a place to stay.

“I mean, there was one building in Azle that was three different banks in the time that I’ve been there… and their fees were outrageous.”

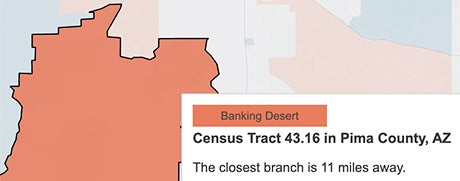

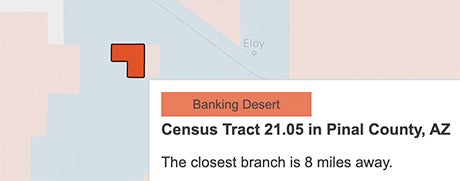

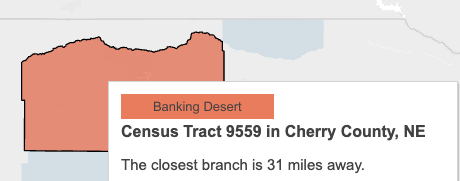

A banking desert is a census tract without a bank branch within two to 10 miles depending on the community’s size, according to Fed Communities, a collaboration among the 12 Federal Reserve Banks. At first glance, anyone who’s well versed in transacting online might not fully understand the pain of having no nearby branches. There are countless online-only banks that offer high yields and low fees, as Bankrate’s reviews and reporting demonstrate.

However, an investigation by Bankrate — spending two days in separate “deserts,” interviewing seven residents, surveying 16 experts and examining government data — reveals high costs for people left behind by the rise of online banking if they don’t have reliable Internet access or aren’t comfortable using this new technology.

These costs are highest in banking deserts. Without a nearby branch, people resort to banking in places that give them a bad deal: expensive check-cashing services, predatory payday lenders, used car lots or high-interest pawn shop loans. For folks like Holmsley, these high-cost alternatives to traditional banking aren’t just inconvenient expenses. They’re an unavoidable strain of daily life that can leave people battling debt instead of building wealth.

Life in America’s banking deserts

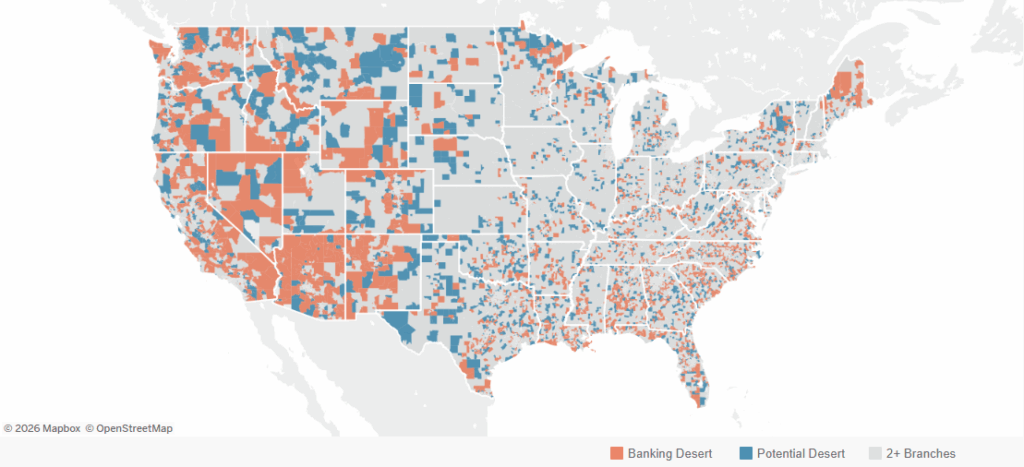

About 12.3 million Americans live in banking deserts — roughly the size of Illinois’ population. Another 11.2 million reside in potential deserts, thanks to big banks’ ever-quickening race to optimize their branch locations for profit. Between 2019 and 2025, in part fueled by the COVID-19 pandemic, branch locations fell by 6.6%, and the number of people residing in banking deserts increased by 785,000.

As reporters at Bankate, we realize that banking deserts aren’t a new phenomenon. Yet the fact that they’re still causing harm to consumers means they require a new look through a fresh lens.

Our goal is to shine a light on the institutions taking advantage of banking desert residents — and where we can, hold them accountable for it. And we’re committed to documenting the experiences of those who, like Holmsley, are negatively impacted — and empowering them. Thankfully, some solutions are in the works, but they’re not yet enough to protect everybody.

Holmesly has experienced the burdens of living in banking deserts

Holmesly’s Azle, Texas (U.S. Census Tract 1404.15 in Parker County) is officially a banking desert, according to the Federal Reserve’s banking deserts dashboard. Fed data shows that the number of bank-barren towns is still growing — albeit more slowly than during the pandemic — and includes some areas you might be surprised by.

Like anyone, Holmesly, who currently lives in a rent-to-own RV working 40 to 70 hours per week as a caretaker, needs banks. If she can find one to refinance her upside-down auto loan, her goal of buying a property — or at least finding a piece of land to park her RV for good — would be more realistic.

“There’s no place out in Azle except for used car lots, stuff like that,” she says.

“And the banks out here, it’s like the little bank inside Walmart. There’s no credit unions or anything like that anywhere near.”

Not having a traditional bank branch nearby comes with a load of costs, some that can be named in dollars and cents and others that can’t.

Lack of in-person assistance

Among people who don’t have an online savings account, 45% say they prefer access to a branch, Bankrate found. Without a nearby branch, you miss out on the opportunity for in-person transactions — for example, the chance to talk with a teller if you’ve overdrawn an account or been the victim of bank fraud.

“I love those stories where a bank teller, by the third time that the elderly person came in and got a money order for ten thousand dollars, and they start to ask questions: ‘Hey, do your kids know about this? Where are you sending this money?’” says Sam Hohman, the CEO of debt counseling agency Credit Advisors Foundation.

The quality of in-person assistance adds another layer to the banking desert conversation, though. A physical structure is one thing, but what’s really missing from banking deserts is the offerings that take place inside. That’s the message from Hohman, whose organization has partnered with First National Bank of Omaha to put credit counselors in the branch lobbies of lower-income areas.

If your bank [has] the brick and mortar, but they’re not really offering any services, does it really matter that they’re there?

— Sam Hohman, CEO, Credit Advisors Foundation

The service is critical because it can cover your blind spots — we all have them. Just by talking it out with a teller, banker or branch manager, you might learn that you have more loan or deposits options than you initially realized. They could help you understand, for instance, the value in securing auto loan preapproval from reputable financial institutions before you walk onto a used car lot and accept its financing at face value.

Money orders and check-cashing fees

Those without a checking account or a nearby bank branch often need to resort to currency exchanges for money orders or check cashing — and there’s usually a fee involved. Such providers often charge $2 to $8 to cash a check, Bankrate data shows — although cashing larger checks may come with a higher fee or a set percentage of the check’s amount. Holmesly relied on Cash App and its $2.50 ATM withdrawal fee (on top of the ATM operator’s cost, among other surcharges), to her detriment, she says.

These fees add up over time: A full-time worker without a checking account could potentially save up to $40,000 during their career by relying on a lower-cost checking account instead of check-cashing services, the Brookings Institution reported in 2008. When factoring in inflation, that’s the equivalent of around $60,000 in 2025.

Becky House, director at nonprofit credit counseling agency American Financial Solutions, works with clients without easy access to banks.

“We have a client who lives in the city, but getting to a bank is difficult due to transportation, work and family obligations. She cashes her paycheck at a local store and uses money orders to pay bills. All of those activities cost her extra money… It works, but it’s costly and limits her ability to save or build credit.”

— Becky House, Director of Strategic Initiatives, American Financial Solutions

Payday loans and other high-interest borrowing

Unbanked consumers in banking deserts have reduced access to conventional loans or credit cards, so some resort to high-interest payday loans. For this predatory form of financing, a borrower gives the lender a personal check for the loan amount, plus a finance charge, and the lender agrees not to cash it until the borrower’s next payday.

A typical two-week payday loan with a fee of $15 per $100 is roughly equivalent to an APR of nearly 400%. Credit card APRs, on the other hand, average just under 20% APR, according to Bankrate data.

At the typical charge of $15 per $100, a $300 payday loan would cost you $345 to pay back, per the CFPB. What’s more, 4 out of 5 payday loans are rolled over or renewed within two weeks, the agency reported years ago. Such a rollover could bring the same loan to a new balance of $390. According to the CFPB, that’s effectively a $90 charge for borrowing $300 for just four weeks.

Consumers who aren’t underbanked have access to a number of safer borrowing options, including payday alternative loans (which typically have APRs capped at 28%) from credit unions. They might even be able to access a personal loan with a more reasonable interest rate on their own or by piggybacking onto the better credit of a family member, if necessary.

ATM fees

Say you bank with a smaller financial institution but don’t have in-network ATMs nearby. If you need cash, you might have to visit an out-of-network ATM, which often comes with two fees:

- A surcharge from the bank that owns the ATM

- A fee charged by your own bank for using an ATM not in its network

Combined, these two charges have reached a record high average of $4.86 in 2025, according to Bankrate’s Checking Account and ATM Fee Study.

Lost interest and lack of security

Keeping emergency cash under your mattress or in a cookie jar, rather than in a high-yield savings account, means you’re losing out on earning interest. What’s more, money kept at home is at risk of becoming lost, stolen or destroyed by a natural disaster — whereas money in a bank that’s insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC) or a credit union insured by the National Credit Union National Credit Union Share Insurance Fund (NCUSIF) is protected.

Holmesly’s not alone: Banking deserts impact many consumers deeply

While it’s difficult to generalize the harm caused by banking deserts, reputable financial institutions have been more likely to close branches in parts of the U.S. where lower-income, Asian, Black, disabled and mixed-minority communities live, according to the Philadelphia Fed’s February 2024 report. This is despite the now-five-decade-old Community Reinvestment Act that sought to eliminate redlining.

| U.S. Census Tract | Percent of population living in deserts | Average distance to nearest bank (miles) |

| Rural | 2.6 | 19.5 |

| Suburban | 4.7 | 7.8 |

| Urban | 2.8 | 2.8 |

| Lower-to-middle income | 3.2 | 10.2 |

| Middle-to-upper income | 4.0 | 7.6 |

| Majority American Indian/Alaska Native | 46.4 | 30.6 |

| Majority Asian | 0.5 | 2.2 |

| Majority Black | 2.8 | 5.6 |

| Majority Hispanic | 2.8 | 7.1 |

| Majority White | 4.3 | 7.8 |

| Lower broadband access | 6.1 | 10.8 |

| Older residents | 4.8 | 9.1 |

| Disabled residents | 5.8 | 9.4 |

| Source: Philadelphia Fed | ||

Many of these groups, as well as rural and older consumers, are more likely to bank in person than their peers, according to a survey from the FDIC. Take away the bank, and they may have nowhere to go — or no way to get there.

Not having banks, where they can reach them easily, essentially cuts them off from banking, because they [may] not have transportation to travel to other areas to access those services.

— Barry Coleman, VP of Program Management & Education, National Foundation for Credit Counseling

“So, I think it’s sort of a double whammy,” Coleman continues. “It’s not only the fact that [banks] aren’t in their neighborhoods, but they don’t have, in many cases, the means to go outside of their own neighborhoods to access those services.”

How often do you need to visit your bank?

About half of consumers (52%) stopped into their primary bank’s branch one to four times in the previous 12 months, according to a 2024 survey by Rivel Banking Research. Baby boomers (4.6 visits annually) led generationally, with Gen Z (3.6 visits) at the bottom.

Native Americans

People living in tribal communities were 12 times more likely to live a banking desert life in 2023 than the average American, according to the Fed’s research. Yet whether they bank online — sometimes a necessity in deserts, if you have Internet access — or travel to a branch, they’re unlikely to find information in their native tongue.

“I’ve walked into a bank to carry out simple transactions on my own, or help other individuals, and have seen tellers yelling at individuals, getting louder with them, thinking that that’s going to help them understand something that they don’t understand because of a language barrier,” says My-Tegia L. Lee, the executive director of the nonprofit Southwest Native Assets Coalition.

I have had to reprimand them and tell them, ‘You have Navajo-working staff, but not Navajo-speaking staff,’ and that’s where the comprehension is not happening.

— My-Tegia L. Lee, Executive Director, Southwest Native Assets Coalition

Small business owners and entrepreneurs

Whether you’re running a business or starting one, a lack of nearby bank branches can make it difficult to obtain financing or securely store cash earnings.

Earlier in his career, as part of researching the impacts of federal Community Reinvestment Act legislation, Consumer Federation of America director of financial services Adam Rust literally got into the weeds of banking deserts and in rural North Carolina. Rust recalls hearing from a well-off individual from Northampton County who was concerned that his bank, PNC, was closing up.

“We heard, similarly, from the chambers [of commerce] and the local business communities that when the bank branch leaves town, it says, effectively, that that town is no longer in business,” Rust says.

Once you lose your last branch bank, how do you come back from that?

— Adam Rust, Director of Financial Services, Consumer Federation of America

The South has been hit hard by desertion, according to the CFPB. In a place like rural North Carolina, losing local bank branches could mean losing local lenders who understand farm credit or the agricultural industry better than national branches without that expertise. It might also mean daily inconvenience — and insecurity — for cash-based businesses.

Many of these businesses “rely on bringing that bag of cash to the dropbox in the evening… And if you have to drive it a mile and a half, that’s one thing,” Rust says. “If you have to drive it 25, 30 miles, that’s totally different.”

What it feels like to live in a banking desert

“Someone might live in what we call a banking desert that doesn’t feel like they live in one. And there are also folks who might live in a place that feels like a banking desert to them that we’re not calling a banking desert because of the way that we measure things.”

— Alaina Barca, Community Development Research Associate, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia

Therein lies the catch of banking deserts. Their definition is black and white. But their impacts can be opaque and, Barca says, vary from one community to the next.

When I drove the 64 miles from my home in Tucson, Ariz. to the Federal Reserve-recognized banking desert of Arivaca, one my first stops was the tiny town’s lone grocery store, Arivaca Mercantile.

I stepped inside to ask about the ATM, and the clerk, Shane Miller, jogged over to it. After checking the machine, Miller called back to me, “Yes, it still has cash.” When he saw my confused look, he added, “It often runs out.”

That ATM is the only place to get cash in the town, aside from the bar across the street, La Gitana, that offers cash-back. When I asked Miller, who was born and raised in Arivaca, whether any of his neighbors were negatively impacted by living in a banking desert, he could only think of one or two residents that the grocery store makes an exception for and cashes their checks.

Solutions taking shape across the banking landscape

On-your-smartphone banking might seem the obvious solution to the challenge of banking deserts, but the reality is more nuanced. Not every American is adapting at the same pace, says Barca. Many don’t have broadband or device access — or the digital skills to transact online. Others are fearful of making money decisions without first talking to a human. Put yourself in the shoes of someone like Holmesly, who distrusts banks.

Finding an online bank can seem pretty hard, just sounds like a lot of work, or sketchy. They might think, ‘Oh, I don’t want to be taken advantage of.’

— Todd Christensen, Financial Counselor

All that said, various businesses and other organizations are helping mitigate the problem of desert life by making financial services more readily available to the underbanked. These include:

Mobile branch centers

Desert solution: Brings the bank to you, wherever you are

Some banks and credit unions send trucks that serve as branches to underserved communities so residents can make deposits, withdrawals or other transactions. These vehicles visit designated stops regularly and are often equipped with tellers and ATMs.

PNC Bank, for example, offers mobile branches that run on continuous routes, with stops near food banks and transitional housing services. Customers can visit these branches to open accounts, receive debit cards and apply for credit cards and home equity loans, says Chris Hill, senior vice president, mobile branch channel manager at PNC.

We work with local communities in the cities we serve to identify the best opportunity to serve the greatest number of community members that we can with laser focus on low- to moderate-income neighborhoods.

— Chris Hill, Senior Vice President, Mobile Branch Channel Manager, PNC

Money tip:

Banks that have operated mobile bank branches include PNC Bank, U.S. Bank, Comerica and Centennial Bank — as well as various community banks and credit unions.

Credit unions

Desert solution: Offers strong customer service, even if it’s remote

As not-for-profit banks owned by their members, credit unions often deliver higher savings rates and lower loan rates than traditional banks. Because they often serve members of a local geographic area or a given profession, credit unions are known for providing more personalized customer service and resources (note that, for this reason, not everyone is eligible to join every credit union).

An example is Denver, Colorado-based Westerra Credit Union, which offers standard banking products but also helps connect its members with non-banking resources such as a local food bank and a homeownership coalition.

“That’s where credit unions really excel — providing access where banks and the traditional financial industry don’t usually go. That’s really what we were founded upon, where our mission is established and where we shine.”

— Anneliese Elrod, Chief Operating Officer, Westerra Credit Union

Community Development Financial Institutions

Desert solution: Could be a better fit if you don’t meet traditional criteria imposed by banks, credit unions

Low-income residents in underserved areas often face difficulties in getting a loan to buy a home or start a business. One resource they can turn to for funding is a Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI).

An organization can receive federal funding and become a certified CDFI by having a community development mission and targeting at least 60% of its financing activities to low- and moderate-income populations or underserved communities. Those looking to find a CDFI with services in their area can use the CDFI locator tool.

Some CDFIs serve specific segments of the population — and can serve them remotely, even via simple phone calls that walk clients through an online interface. “We’re unique to other CDFIs,” says Lisa Jones, a director of the fully-remote Northwest Access Fund, which serves people with disabilities. “We have five certified disability benefits planners on staff who help people make educated moves financially — employment-wise, housing-wise and helping them better understand how the disability benefits system works. Credit-building is a huge thing. Even subsidized housing requires credit.”

They don’t feel like that they were heard [at their bank] or that they were given the time to understand the products fully. Almost everyone who gets our loans have already been denied a loan at a bank.

— Lisa Jones, Director of Outreach and Partnerships, Northwest Access Fund

Bank On-certified checking accounts

Desert solution: Replaces check-cashing, other fee-based services with a safe, secure account

Lack of access to affordable banking can be a barrier of entry if you’re underbanked. One initiative that aims to mitigate this is called Bank On, which certifies checking accounts when they meet standards such as having no overdraft fees, low minimum opening deposit requirements and low or no monthly maintenance fees.

We recognize that it’s hard to bank people for a lot of reasons, whether it’s trust, distance to a bank or having a past where they’ve had an account closed.

— David Rothstein, Senior Principal, Cities for Financial Empowerment Fund

“[In forming Bank On], we recognized that we really needed to make sure the field was ready for national account standards,” continues Rothstein. To date, nearly 500 checking accounts have earned the Bank On certification, encompassing financial institutions of all sizes, including megabanks like Chase, Wells Fargo, Bank of America and U.S. Bank. You can visit the BankOn website to find certified accounts available near you.

Why we ask for feedback

Your feedback helps us improve our content and services. It takes less than a minute to

complete.

Your responses are anonymous and will only be used for improving our website.

Help us improve our content

Read the full article here